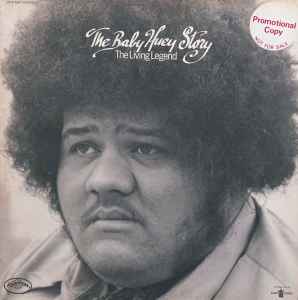

Baby Huey – The Baby Huey Story - The Living Legend

Más imágenes

Sello: Curtom – CRS 8007

Formato:

Vinilo, LP, Album

País: US

Publicado: 1971

Género: Funk / Soul

Estilo: Soul, Funk

Lista de Títulos

Ocultar créditos

A1 Listen To Me

Written-By – M. Johnson*

Written-By – M. Johnson* 6:35

A2 Mama Get Yourself Together

Written-By – J. Ramey*

Written-By – J. Ramey* 6:10

A3 A Change Is Going To Come

Written-By – S. Cooke*

Written-By – S. Cooke* 9:23

B1 Mighty, Mighty

Written-By – C. Mayfield*

Written-By – C. Mayfield* 2:45

B2 Hard Times

Written-By – C. Mayfield*

Written-By – C. Mayfield* 3:19

B3 California Dreaming

Written-By – J. Phillips*

Written-By – J. Phillips* 4:43

B4 Running

Written-By – C. Mayfield*

Written-By – C. Mayfield* 3:36

B5 One Dragon Two Dragon

Written-By – J. Ramey*

Written-By – J. Ramey* 4:02

Créditos

Art Direction – Michael Mendel

Producer – Curtis Mayfield

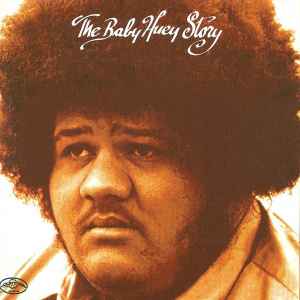

Baby Huey – The Baby Huey Story

Sello: Sequel Records – NEBCD 405

Formato:

CD, Album, Reissue, Remastered

País: UK

Publicado: 1999

Género: Funk / Soul

Estilo: Soul, Rhythm & Blues

Lista de TítulosOcultar créditos

1 Listen To Me

Written-By – Michael Bruce Johnson

Written-By – Michael Bruce Johnson 6:39

2 Mama Get Yourself Together

Written-By – James Thomas Ramey

Written-By – James Thomas Ramey 6:11

3 A Change Is Going To Come

Written-By – Sam Cooke

Written-By – Sam Cooke 9:24

4 Mighty Mighty (AKA Mighty, Mighty Children Part 2)

Written-By – Curtis Mayfield

Written-By – Curtis Mayfield 2:46

5 Hard Times

Written-By – Curtis Mayfield

Written-By – Curtis Mayfield 3:20

6 California Dreamin'

Written-By – John Phillips

Written-By – John Phillips 4:46

7 Running

Written-By – Curtis Mayfield

Written-By – Curtis Mayfield 3:36

8 One Dragon Two Dragon

Written-By – James Thomas Ramey

Written-By – James Thomas Ramey 4:04

Bonus Tracks

9 Mighty Mighty Children (Part 1)

Written-By – Curtis Mayfield

Written-By – Curtis Mayfield 2:27

10 Running (Previously Unissued Mono Edit)

Written-By – Curtis Mayfield

Written-By – Curtis Mayfield 2:50

11 Hard Times (Previously Unissued Mono Mix)

Written-By – Curtis Mayfield

Written-By – Curtis Mayfield 3:20

Compañías, etc.

Copyright fonográfico ℗ – Sequel Records

Copyright © – Sequel Records

Licencia de – Curtom Classics Inc.

Publicado por – Warner Chappell Music Ltd.

Publicado por – ABKCO Music

Publicado por – MCA Music Ltd.

Remasterizado en – DigiPrep

Diseñado en – MC80 Graphic Design

Créditos

Artwork, Design [Reissue] – Julien Potter, Paul McEvoy

Bass [The Babysitters] – Dan Alfano

Bongos [The Babysitters] – Plato Jones*

Flute [The Babysitters] – Othello Anderson

Guitar [The Babysitters] – Dan O'Neil (2)

Keyboards [The Babysitters] – Melvin Jones*

Lead Vocals – Baby Huey

Liner Notes – Peter Burns (2)

Liner Notes [Original] – Marv Stuart

Musician [The Babysitters] – Jack Renee, Phillip Henry

Organ [The Babysitters] – David Cook (4)

Percussion [The Babysitters] – Reno Smith

Photography By – Gil Ross

Producer – Curtis Mayfield

Remastered By – Warren Salyer

Tenor Saxophone [The Babysitters] – Byron Watkins

Trumpet [The Babysitters] – Alton Little, Rick Marcotte

Notas

Originally released in March 1971 [Curtom CRS 8007]

Track 9 originally released as single A-side in 1969 [Curtom CR 1939]

Track 10 previously unissued mono edit

Track 11 previously unissued mono mix

Recorded in Chicago, IL, 1969

Tracks published :

1, 2, 4, 5 and 7 to 11 Warner Chappell Music Ltd

3 ABKCO Music

6 MCA Music Ltd.

Compiled and produced by Curtis Mayfield, this classic 1971 funk-soul-psych-rock rarity is remastered from original Curtom tapes and adds two previously unissued mixes.

All information are taken from CD booklet, including liner notes

Musician [Personnel]

Baby Huey &

Alton Little,

Byron Watkins,

Dan Alfano,

Dan O'Neil (2),

David Cook (4),

Jack Renee,

Melvin Jones*,

Moose (13),

Othello Anderson,

Phillip Henry,

Plato Jones,

Reno Smith,

Rick Marcotte

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Baby_Huey_%26_the_Babysitters

Original line up early - mid 60s

James Ramey: lead vocals

Johnny Ross: lead guitar

Melvyn Jones: trumpet and organ

Larry Sales: bass guitar

Dennis Moore: drums

Added later

Byron Watkins: saxophone

Charles Clark: saxophone

Late 60s members

James Ramey (Baby Huey): lead vocals

Melvyn Jones: keyboards

Othello Anderson: flute

Rene Smith: percussion

Byron Watkins: tenor saxophone

Rick Marcotte: trumpet

Alton Littles: trumpet

Danny O'Neil: guitar

Dave Cook: organ

Dan Alfano: bass guitar

Plato Jones: bongos

Additional personnel

Jack Renee: unknown instrument

Philip Henry: unknown instrument

Moose (nickname): unknown instrument

http://www.garagehangover.com/baby-huey-baby-sitters/

http://highwayscriberybooks.blogspot.com/2010/02/forty-years-with-blues-legends-by.html

Tuesday, January 5, 2010

"Forty Years with the Blues Legends," by Melvin (Deacon) Jones

the highway scribe would like to gather up his red Fender Starcaster and his 22 watt amplifier and go over to Deacon Jones’ place for a jam.

That way he would be associated with Jones, and all the legends Jones has jammed with and recounted in his charming autobiography,"The Blues Man: 40 Years with the Blues Legends."

That way the highway scribe could tell his grandchildren he’d jammed with a guy who’d jammed with all those famous guys.

Which would be an improvement on the scribe’s current career trajectory.

But seriously, Jones’ story is a lot like the blues itself. It's sad, but it sounds good so that you don’t know whether to laugh or cry.

“I guess the only reason that I haven’t given in is because I don’t know how to quit. I’m sort of like a Timex watch; I take a licking, but I keep on ticking. I just hope and pray that one day the sun will shine on Deacon Jones and I’ll finally get lucky and hit it big. It seems that every time I’m near the top, something goes wrong and I fall down again.”

Here’s a gentleman who has played with Baby Huey and The Babysitters, The Impressions, Curtis Mayfield, John Lee Hooker, Freddie King, Elvin Bishop, Buddy Miles, Greg Allman, Willie Dixon, Carlos Santana and a veritable who’s who? of sixties/seventies music stars.

It’s a classic story about the music industry.

Says Deacon (with the help of an able M. Jonathan Hayes):

“In 1965, we finally settled into a regular gig at the Thumbs Up on the North Side. They started us off at one night a week, $5 each, and all we could drink. And everyone wants to know why I got to be an alcoholic.”

Keeping in mind that Melvyn’s story (that’s his real name) winds through the early ’60s and is still unspooling, drugs and booze are a part of things, given the predilections of his lively and special generation.

Here’s an accounting of an all-star jam with Buddy Miles, Noel Redding [Hendrix’ bassman] Eric Clapton, and Deacon’s boss at the time, Freddie King.

“The music and the vibes were just blowing everyone away. Eric was a monster on guitar but he was pretty blitzed. During the performance, he came over and sat down on the organ bench next to me on my right side. It was pretty cool except that he started leaning into me while I was trying to play, bumping into my right arm during my solos. I was whispering to him out of the side of his mouth. “ Eric, Eric, I can’t play.”

“Oh, sorry mate, sorry,” he would gurgle and sit up straight for a moment. It was hilarious. Soon he was tilting to the side gain, leaning into me."

That was the joy, but in the crazy world of endless travel, shoestring budgets, and reckless lifestyles, there was much sadness for Deacon, too.

Jones, who was born in Richmond, Indiana while the gale winds of World War II were blowing full force, headed north to Chicago at a tender age with a very large fellow from the neighborhood named Jimmy Ramey, who took the show name of Baby Huey and sang for “The Babysitters” of which Deacon formed a part.

Maybe you have to be a music junkie to enjoy Jones’ stories about how this guy did not like to practice, or that guy couldn’t remember the lyrics, or couldn’t play lest he was stoned out of his mind or had some fried chicken first, but the book contains lots of personal peculiarities of people elevated by stardom who are really, just people.

Freddie King, for example, was a great lead guitarist, but couldn’t “chord” very well, which is a way of saying he loved the spotlight, but wasn’t crazy about driving the band with a little mundane dirty work.

Ramey, who only knew two numbers when the joint venture began (“Peanut Butter” and “Wiggle Wobble”), “was kind of lazy when it came to learning new songs. I told him he had to know more songs if he was going to make it with any band. We learned, ‘Go, Gorilla, Go’, by the Ideals, and some Four Tops, James Brown, Stevie Wonder songs. The number one song we learned that always got the crowd going was Stevie Wonder’s ‘Uptight, Everything is Alright’ .”

highwayscribery includes the anecdote because it shows the book for what it is: a recounting from the stage and from the rehearsal room by a craftsman in pop and blues, rather than a conceptual rambling about the black roots of music, slave canticles and what have you.

Deacon went on stage and played songs. That was and is his life and through him the reader learns the nuts and bolts of performing at Harlem’s famed Apollo Theatre and how perilous it could be when the organ player printed up a few shirts to make an extra buck selling them outside the show.

Ramey liked his drugs apparently, though Jones never specifies. He recounts how he’s was having cereal for breakfast one morning at Baby Huey’s place when his “drug kit” fell out of the Wheaties box when Deacon turned it over to fill his bowl.

“All of a sudden there was a loud demanding knock at the door. A big voice yelled, ‘ Chicago Police - open the door - now.’ Ramey calmly dropped his kit back into the box and the wax paper on top of it. Someone opened the door and in comes all these burly task force narcotics officers with bullet proof vests, holding semi-automatic guns and big pistols. One of them barked, ‘ Freeze. Don’t noboby move!’

“Ramey looked up and said nonchalantly, ‘ Can I finish my breakfast?’

“ A cop said, ‘ Yeah smart ass. Go ahead’.”

“The man” looked everywhere in that place, except the Wheaties box.

But Ramey could not escape himself and died of an overdose just when Curtis Mayfield was about to make him a star.

A lot of tragedy. Dennis Moore, drummer for The Babysitters dropped out of school so he could go to Paris with the band. There they were a smash with the crowde and press, but had failed to get a contract and came home empty-handed.

For Moore, it was worse. The Viet Nam War was happening and leaving school cost him his draft exempt status. He served, but came back and found he could not play anymore and killed himself.

“A drummer is the only musician who can’t put his instrument away for a couple of years an come back. Everyone else can quit and come back and continue where he left off but the drummer.”

And there’s lots more where that came from. Deacon got his job with the Impressions when the backing band was killed in a car accident rushing to a gig, weighted down with musical equipment.

Jones was hitched well to Freddie King’s rising star, although there were always the attendant ambiguities of the artistic life.

They opened for Grand Funk Railroad at the height of that band’s popularity, which, for those of you who don’t remember, was considerable. The ticket played Madison Square Garden and rocked the house, according to Deacon who made $35 for the night.

“It didn’t matter that it was a huge show before a zillion people with news reporters, celebrities, flashbulbs clicking the whole night, interviewers in our dressing room after the show, pictures in the papers the next day. The fans didn’t know that I didn’t have a nickel to my name. They didn’t know that I lived hand to mouth at home and on the road. I probably slept on a box spring that night. I was an organ sideman with nothing living the glamorous life on the road with a superstar.”

But even that came to an end. Again, with superstardom within a finger’s length, King died at the age of 41, leaving Jones to start all over again.

And start he did, introducing himself to the legendary John Lee Hooker and asking to sit in for one night that turned into many.

Again, Jones was close, but left without that fat cigar. He has some complaints about these big boys, their broken promises, the waiting until the next big break that never came, but that’s the arts. Deacon takes his space to gripe, but it is only a way of completing a picture mostly filled with the privilege of having talent and shared it with others in similar possession.

Hayes lets Jones tell it his way and Jones tells it well, in an authentic voice, carrying many a keen observation.

It’s not all music because when you’ve lived through such times and such people, you’ve been a part of history, too. A historical event is something that encompasses everybody, not just the direct protagonists.

For instance, while students and radicals were demonstrating at the 1968 Democratic Convention in Chicago, Mayor Richard Daley declared martial law.

“I was driving my station wagon one night, back to the house where we were all living near Hyde Park. I pulled up to a stoplight and heard chinka chinka chinka right next tome and I thought, what the hell is that? I looked over and a Sherman tank had pulled up along side of me - on Garfield Boulevard. A soldier’s head was sticking out of the little hole on the top of the tank and he was looking over at me. He pointed to his watch and I yelled out, ‘I know, I got 10 minutes.’

“He said, ‘You got far to go?’

“I said, ‘Just two minutes and I’ll be home.’

“He said, ‘You better hurry,’ and hurry I did.”

Deacon Jones is a black man and the story is laced with occurrences that could happen to a black man, without the organmeister necessarily pointing it out. In just one anecdote does he air his despair.

It involves a car trip from Los Angeles to South Carolina with a quarter pound of weed stashed somewhere in the vehicle and a New Mexico State patrolman. Without probably cause, but highly suspicious, the officer is unable to break the cool musicians’ united front.

Sending Jones back to the car, the cop begins to work over drummer Jeff Miller, a white guy, trying to “divide and conquer,” offering to let him go and arrest the black guys if he’d share the secret about where the drugs were.

“[A]ny time you’re looking at a police officer who has an American flag on his collar and handcuffs for a tie tac, he’s not going to take a bag of weed over there and dump it out. And by trying to divide us racially, you could tell he was a racist. He didn’t like two white guys and two black guys traveling together...

...He was the nightmare of America."

https://eu.pal-item.com/story/news/local/2017/07/07/blues-legend-richmond-dies-california/460061001/

MIKE EMERY | The Palladium-Item

Melvyn "Deacon" Jones switched from trumpet to organ and embarked on a renowned career playing the blues on a Hammond B3.

Jones, 73, a Richmond native, died Thursday evening in Hollywood, Calif., according to his website.

Tributes from musicians who called the organist, composer and arranger a mentor, a genius and a legend stacked one after the other on Jones' Facebook page, including a post from his companion and manager, Pamela Hill. She said she enjoyed 25 years "of sharing life, joy, fun, happiness, travel and lots of music" in some of the 42 countries where Jones played.

At Richmond High School, Jones, who graduated in 1962, played in the band for Wilburn T. Elrod, the orchestra for Ralph Burkhardt and the pep band. In addition, Jones played with a dance band that performed at the YMCA.

Jones, the brother of jazz drummer Harold Jones, who backs singer Tony Bennett, was among the Richmond musicians forming rock 'n' roll band Baby Huey and the Babysitters, playing trumpet in the band that eventually progressed to Chicago for five years of five-night-a-week performances. He also studied at the American Conservatory of Music in Chicago and the University of Chicago, according to the biography on his website and Facebook page.

Melvyn "Deacon" Jones, right, played trumpet for Baby Huey and the Babysitters, a band formed in Richmond that moved to Chicago.

SUPPLIED

As an organist, he spent 18 years as band director for blues legend John Lee Hooker. Jones' original composition, "We'll Meet Again," was part of Hooker's "Chill Out" CD that won a Grammy in 1996.

Jones also toured and recorded with artists such as Curtis Mayfield, Freddie King, Eric Clapton, Carlos Santana, Joe Cocker, Stevie Ray Vaughn, Greg Allman, Dr. John, Lester Chambers and Eddie Money. Based in Los Angeles, Jones recorded his own CDs and was still playing with The Deacon Jones Blues Band and The Bucket of Blues Band.

South Bay Blues Awards and San Francisco Blues Society chose Jones as keyboard player of the year in 1991, and Real Blues magazine selected him the top blues keyboard player in 1996, 1997 and 1998.

Jones was born Dec. 12, 1943, in Richmond, according to his biography, to Juanita and Jay Jones.

He said in a 2010 Palladium-Item article that he experienced two miracles as a child. The first came when he was 5 years old and had an acute case of polio. A faith healer in Connersville gave him a jar of water and told him to drink a glass a day and say the Lord's prayer for seven days.

"On the eighth day, I was walking," Jones said.

The second miracle came after he ate red, green and yellow mulberries from a backyard tree. Jones' appendix exploded and he remained in a coma for three days and three nights, with doctors telling his parents, "We've done all we can do. It's in God's hands now."

He said his childhood taught him that "God didn't give you a gift to abuse."

Instead, Jones turned his gift into decades of music.